So many ships have so many great stories. I’d like to start highlighting a few of them. Here’s a start:

Toward the end of World War I, the US government needed all the shipping tonnage it could obtain, to move resources to Europe. It looked to the Great Lakes for freighters available there, and among the ones it found there, the last it took was the largest of all, the Charles R. Van Hise. The Van Hise was built in 1900, and was 458 feet long, and 50 feet wide. To get any of these ships from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic meant taking them around Niagara Falls, from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. The way to do that is through the Welland Canal . At the start of the First World War, the Canal had 26 locks, each 270 feet long and 45 feet wide. Most ships that were taken by the US Shipping Board were too long to travel through these locks, so they were cut in half amidships, each end had a bulkhead added to the cut side, and each half was towed through the locks separately. They were then put back together once they’d arrived in Lake Ontario, before heading up the St Lawrence Seaway and on to the Atlantic.

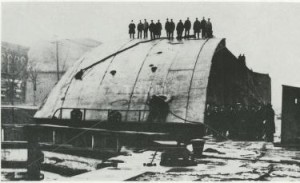

The Van Hise, however, was not only too long, but also too wide: the locks were 45 feet wide but the Van Hise measured in at 50 feet. In a remarkable feat of engineering that has not been repeated, the ship was first cut in half admiships, like previous ships had been. Then she was rotated on her side, using some internal tanks and added pontoons. Since she wasn’t particularly deep, she could be turned on her side, and with her port side now acting as her keel, she was narrow enough to fit through the locks.

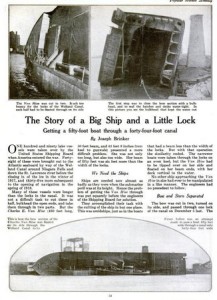

This excellent story (via Google Books) in the March 1919 issue of Popular Science describes how the process was done. The forward section passed through the first lock, as a test, in early December 1918, and the aft section, which was at this point waiting in Buffalo, was to follow in the spring of 1919. Each piece would then be towed through the other locks of the Welland Canal, to get to Lake Ontario. But hostilities had ended, and the need for the ship was negated. So the bow was towed back through the southern-most lock, back to Lake Erie, and the two halves were rejoined at Ashtabula, were the ship was also extended in size.

Van Hise went back to work, and then went through a variety of name changes – A. E. R. Schneider, S. B. Way, J. M. Oag, and finally, in 1936, Captain C. D. Secord. More work continued to change her profile, but she kept working the lakes, up until 1967. In 1968, she was sold to a Montreal scrapping firm who resold her, and in August 1968 she was towed to Spain to be broken up.

Van Hise went back to work, and then went through a variety of name changes – A. E. R. Schneider, S. B. Way, J. M. Oag, and finally, in 1936, Captain C. D. Secord. More work continued to change her profile, but she kept working the lakes, up until 1967. In 1968, she was sold to a Montreal scrapping firm who resold her, and in August 1968 she was towed to Spain to be broken up.

So how did she get through the Welland Canal to head out on her final voyage? Canal construction, running from 1913 to 1932, had reduced the number of locks from 26 to eight, and significantly increased them all in size, to 766 feet long and 80 feet wide – plenty wide enough for the Van Hise’s trip to the breaking yard, nearly 70 years after she’d been launched.

Sources: The story of this remarkable ship first appeared on the MARHST-L discussion list in January 2015. Posters included links to the Popular Science article (linked above), and this extended history of the ship’s life, on the Maritime History of the Great Lakes site. This page from the Great Lakes Maritime Database came via ShipIndex.org, and has this image of a dozen or so men standing on the Van Hise’s starboard-side-acting-as-deck.  Other links from within ShipIndex.org led me to an entry at Bowling Green’s Great Lakes Vessel Online Index, as well as manuscript records for Captain C.D. Secord at Milwaukee County Library System, an image hosted by York University.

Other links from within ShipIndex.org led me to an entry at Bowling Green’s Great Lakes Vessel Online Index, as well as manuscript records for Captain C.D. Secord at Milwaukee County Library System, an image hosted by York University.

(For information on how I tracked down those manuscript records — which is not a simple process — read my entries on making the most of WorldCat record, here.)