I spent September 17 to 19 at the New York State Family History Conference in Syracuse, NY. It’s not too far from home, so I was glad to attend the first one, two years ago, and I certainly looked forward to attending future conferences, which are scheduled for every other year.

Of course I talked with lots of people, told them about ShipIndex, and learned about new sources of content to add, as well.

Here are two examples of searches I did for folks, which I felt were a great example of successes from searching ShipIndex.

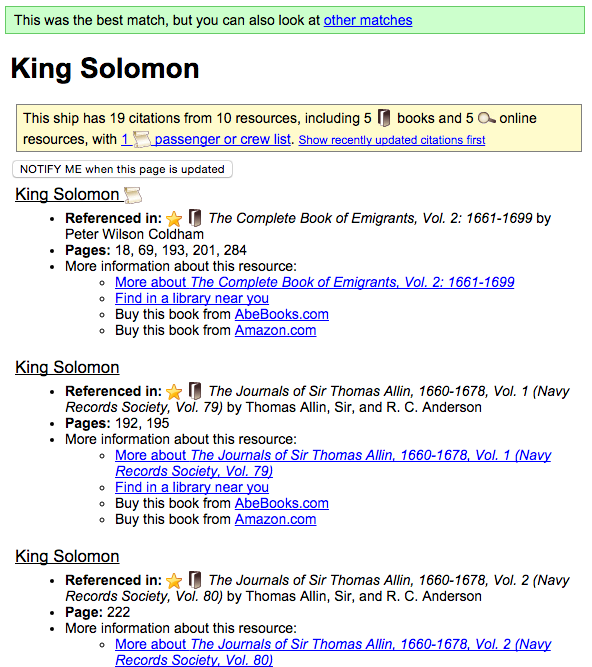

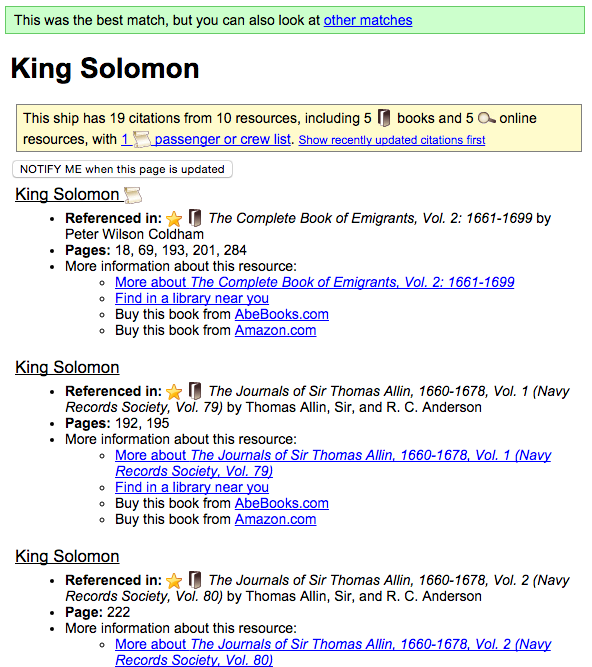

First a woman was looking for information about a ship her ancestors emigrated on, from Holland, in the 1650s. The ship was named “King Solomon”. So I did a search in the full database for “King Solomon” and found the following result:

The entry from Coldham’s book, The Complete Book of Emigrants, makes sense, given the time period. (She said they emigrated in the 1650s; perhaps her dates are off by a decade, or perhaps this doesn’t include the travel of her ancestors but rather travel a few years later.)

But what I was most excited about was the discovery of the mentions in the Navy Records Society volumes. Of course, without checking the actual volumes, we don’t know if this is really the same ship or not, but the dates, the relatively unusual ship name, and the origin (more on that in a bit) all seem to work, so that’s in our favor.

The Navy Records Society has been publishing primary documents in British naval history for the past 130 years or so. The documents they publish go back to the 14th century. While each volume often doesn’t have a lot of ships in them, I feel that these citations are incredibly valuable, because they usually link to primary documents. In this case, it would appear that Sir Thomas Allin mentioned a ship named “King Solomon” in his journals at some point. It may or may not be the ship that these folks were researching, but it certainly seems close enough to warrant a second look.

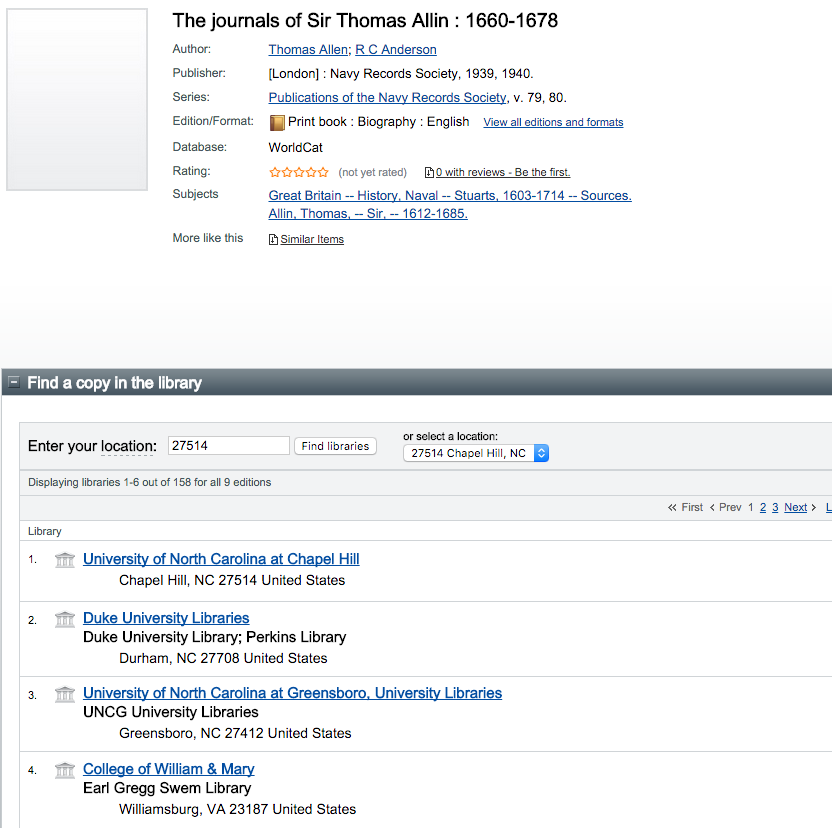

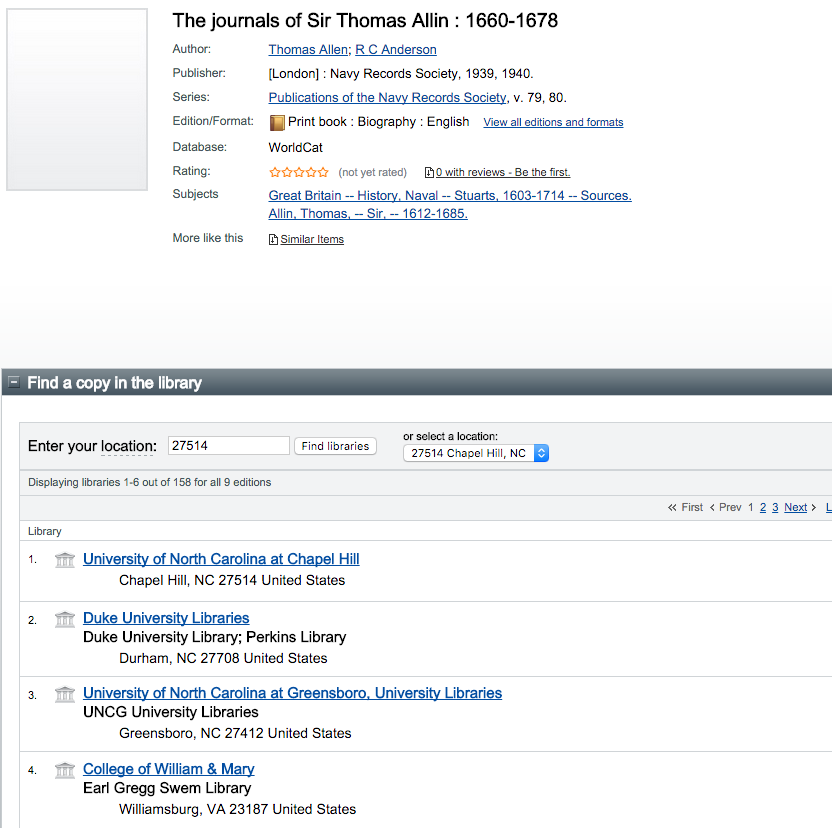

By clicking on the “Find in a library near you” link from the ShipIndex page, we were able to determine that the library University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which is near their home, has these titles. (A junior college in Durham also has the titles, but as a proud Tar Heel and UNC graduate, I choose not to speak its name.)

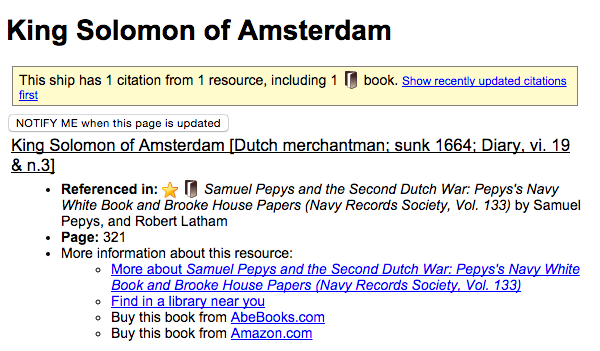

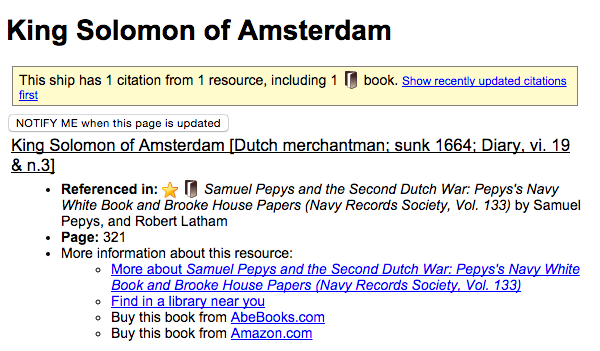

I then took a look at the “other matches” in the green box and found the following citation:

So, a ship with the name “King Solomon of Amsterdam” is mentioned in another NRS volume that covers the same period, apparently in Samuel Pepys’ diary or papers. The name of the ship is probably “King Solomon”, but the city certainly confirms the information about the ship coming from Holland, which the researchers had provided before we started.

I particularly like the fact that we very quickly found citations that certainly appear to be related to the ship the people were researching, from a source far separated from standard genealogical sources. It’s possible that they’re not the same ship, or that there’s nothing relevant to the researchers’ work, but at the same time, it’s quite possible that they’ll discover something quite valuable. This is the kind of serendipitous discoveries that I love to help facilitate.

Here’s my second example. A gentleman sought information about the 19th century ship William Tapscott. From the ShipIndex database, we found multiple citations, from many sources. Some were standard works for that period, such as Fairburn’s Merchant Sail, but others were a bit different. There’s an 1856 article that mentions the ship in the newspaper News of the Day, accessed via Accessible Archives’ “Civil War Collection”. The link to an authority record for the ship, in OCLC, provided the best sources, however.

We found four works about the ship in WorldCat. One is a recent book, of which only 200 copies were printed, about a captain of the ship. Another was a manuscript resource from Utah State University Library, though unfortunately the URL in WorldCat to the finding aid online is broken. It would appear that when USU moved their electronic catalog into the joint Orbis Cascade Alliance of many Pacific Northwest university libraries, their URLs for finding aids were never updated. I went to the USU library catalog to find the correct URL, and their own link also broken – so certainly WorldCat is not to blame here, if USU’s implementation of Encore can’t connect to their own finding aid.

The resource called “Sketches from the Life of Hans Christensen Heiselt” is a small part of the overall collection called “Joel Edward Ricks Papers, 1850-1972”. You can find it via USU’s online catalog, or the Archives West search box. (Interestingly, the Heiselt resource doesn’t appear to be cataloged in the Archives West collection; it’s only listed as part of the Ricks Papers.) From these records, I believe from the original resource is just three pages long, and is in Box 6, Folder 7, of the Ricks Papers.

The other sources were a bit more interesting. One, from the “Ebenezer Beesley papers, 1863-1950,” says it includes “a photostat copy of a handwritten list of passangers (sic) on the William Tapscott in 1859.” This was when the researcher’s ancestor was aboard, so it would certainly be worth viewing this collection, held at Brigham Young University, if the researcher is ever in Provo.

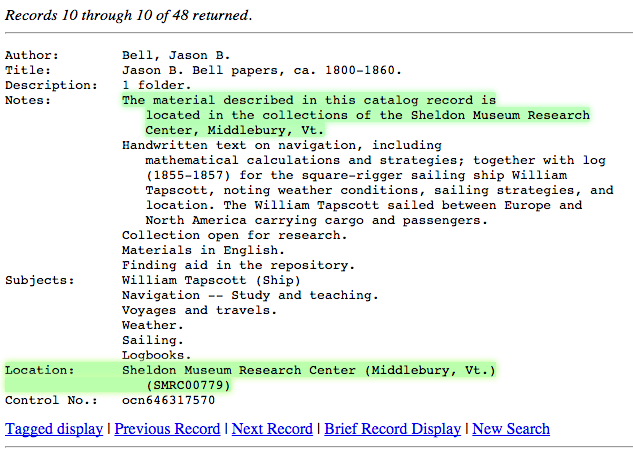

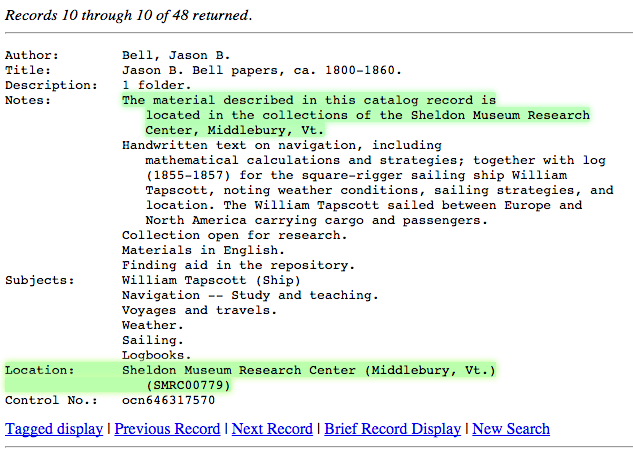

Finally, the “Jason B. Bell papers, ca. 1800-1860” include a “log (1855-1857) for the square-rigger sailing ship William Tapscott, noting weather conditions, sailing strategies, and location. The William Tapscott sailed between Europe and North America carrying cargo and passengers.”

The challenge with this entry is that it does not show where this logbook is held. I have written about how to track down the logbook, in a previous blog post – there’s no way you’d know how to do this without knowing it, so I want to repeat it often. Please take a look at that blog post, and keep it in mind when WorldCat won’t tell you where a manuscript collection is held. Long story short, I searched NUCMC (National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections, searchable at http://www.loc.gov/coll/nucmc/oclcsearch.html) and found the entry, among the 48 results:

When I clicked on “More on this record”, I found the following. (I added the highlighting, to emphasize the location information.)

The record showed me that this logbook is held in the Sheldon Museum Research Center, in Middlebury, Vermont. In looking closer at the “tagged display,” I believe this record was created in July 2010; either way, I’d certainly call the museum library before driving out to Vermont to see it. (And a quick review of the website shows their library is just open to visitors two afternoons a week.)

On an important note, this conference will switch from odd-numbered years to even-numbered years, starting in 2016, so that it’s off-set from the New England Regional Genealogy Conference, which currently occurs in odd-numbered years. That’s a good move on the organizers’ part, I think, and I look forward to returning to Syracuse next fall.

In the end, these two examples showed some of the resources – some monographic, and some manuscripts – that one can find quickly and (mostly) easily through a search at ShipIndex.org. I hope they’ll inspire you to find remarkable resources through ShipIndex, too.