TL;DR: The ShipIndex.org database can now differentiate between disparate ships of the same name, and combine citations using different names for the same ship. We use Wikidata Q-identifiers to do this, and hope that we can help apply Linked Data to maritime history.

This is a very long post about some significant enhancements that we’ve added to ShipIndex.org. For a shorter post about the same thing, that doesn’t go into quite as much detail, see here.

Greetings, from ShipIndex central. It’s been a while since our list blog post, and I referenced some upcoming changes back then. Of course, things have taken a bit more time than I’d expected, but I’m ready to start sharing some of these changes.

Right now, ShipIndex.org has over 3.5 million citations from over 900 resources. If you’re looking for a specific ship with a common name, you’re gonna have a hard time. Looking for a specific “Eagle”? As of today, there are 2,677 citations for ships named Eagle. “America”? There are 2,378 citations. The most common ship names are, in increasing order, “Hope”, “Anna”, and “Maria”, with “Elizabeth” having 3,818 citations, and “Mary” leading by a lot, with 5,072 citations.

Researchers have a big problem in trying to work through those common ship names. And they have a problem when a ship changes its name – it’s still the ship they want to research, but ShipIndex.org doesn’t really connect a user with the ship’s previous or subsequent names. (Well, it did, a bit: if you look at the “America” entry, you can see “related ships” – but how do you know which of the 2,378 citations also refer to Italis, West Point, or Australis?)

What I always wanted was a “unique vessel identifier”. I could bring together citations that refer to the same ship, and differentiate between citations for different ships with the same name. I wasn’t sure how to make that work, until a colleague at my day job suggested using Wikidata identifiers. This was such a great idea, for many reasons.

You’ve all seen the xkcd comic about standards, right? No? OK, here:

Same thing with identifiers. Many already exist – naval hull numbers, IMO numbers, national registration numbers, and others – but none refer to all ships, obviously. I didn’t want to create a new identifier, especially since most of the world wouldn’t use it. Wikidata, however, addresses all of these issues, and most importantly it can make maritime history research easier by using these identifiers across the web. For example, a vessel at a maritime museum, like Mystic Seaport’s Joseph Conrad, has the Wikidata identifier Q1278752. This is a “Q-number”, assigned at random. It is unique to this specific item. The Wikidata entry contains other pieces of factual data about the vessel, including its current location, its builder, and some of its dimensions. Anyone can add to the record about any entry.

Every item or entry (including non-physical concepts) in Wikipedia has a Q-number. Look on the left column for any Wikipedia entry (like the Conrad‘s), and you’ll see an entry under “Tools” that’s labelled “Wikidata item”. That links you to the Wikidata entry for the item in question. Information from Wikipedia is incorporated into Wikidata, and all of the information is available for sharing and using on the web. Look on the right of the Wikidata entry, and you’ll see a list of entries on that subject, in numerous different languages.

(As another aside, note the difference here between Wikipedia and Wikidata. Wikipedia contains textual information and discussion about a topic or item. One subject may have multiple entries in different languages. [The German entry about Joseph Conrad is not just a straight translation of the English one. Nor is the Farsi entry.] Wikidata, on the other hand, is a collection of data – just the facts, ma’am – about the topic. Wikidata does not have foreign-language versions of each data page.)

This Wikidata entry for “Joseph Conrad” is different from entries for the Polish author even though the ship is named after him; from a French army officer with the same name; a US army officer; and more. By using linked data in this way, online systems can better identify the person from the ship, making it easier for researchers to find what they’re looking for, quicker.

Over time, I’ll be able to do lots more with the Wikidata that is available to us, as the Wikidata database grows. Hopefully, the ShipIndex.org data will be easier to find online, plus it will be easier to use, because ships with common names will be better sorted, and ship name changes will be better represented.

Last December, my son and I visited the Cradle of Aviation museum in Garden City, NY. While there, we saw this plaque describing the many different ships in the US Navy named “Hornet”:

This is a great example of what we’re trying to do here in ShipIndex.org – sorting and dividing the many very different ships with the same name. (Note here, though, that this plaque differentiates between the last three versions of USS Hornet, saying that CV-12, CVA-12, and CVS-12 were different ships. They really weren’t; they were the same hull, even if they were refitted for different uses over the last decades of service. I don’t know, but I’d be surprised if Navy veterans who served on CV-12 would feel that they served on a different ship than those who served on CVS-12, for instance.)

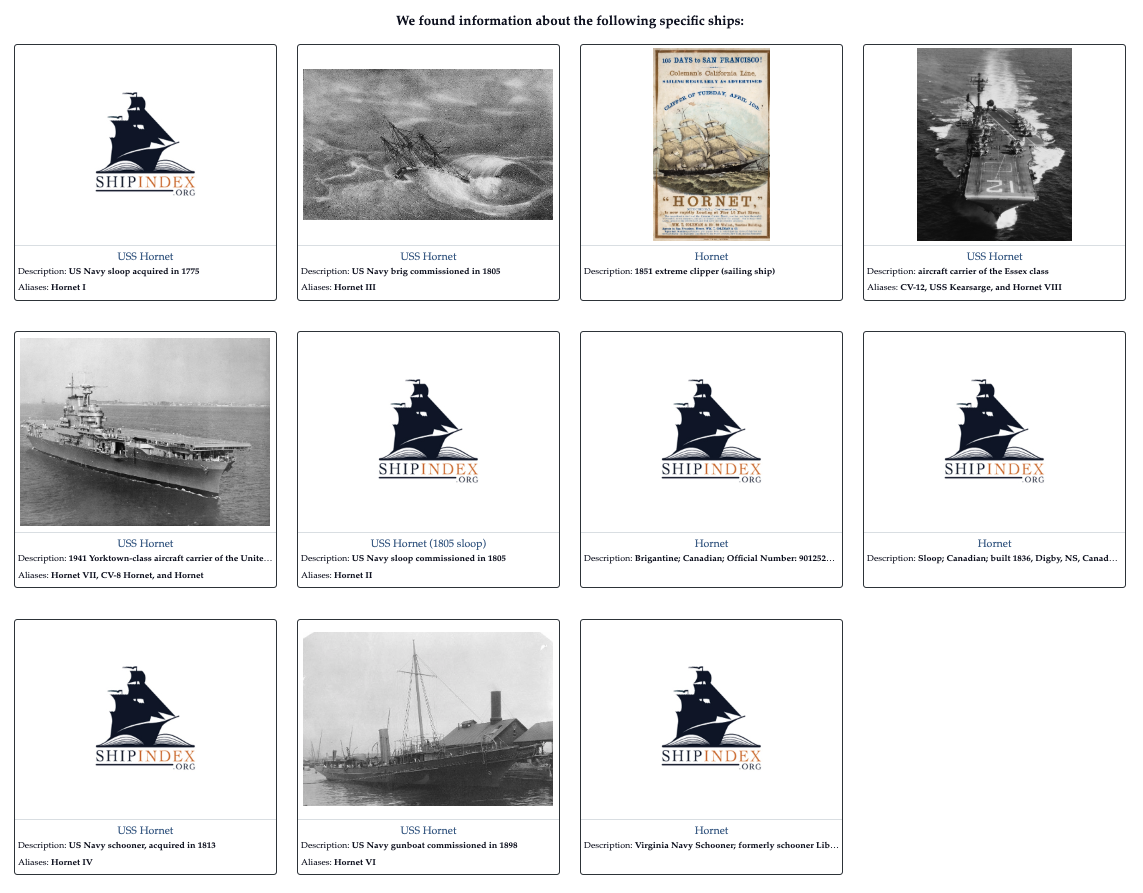

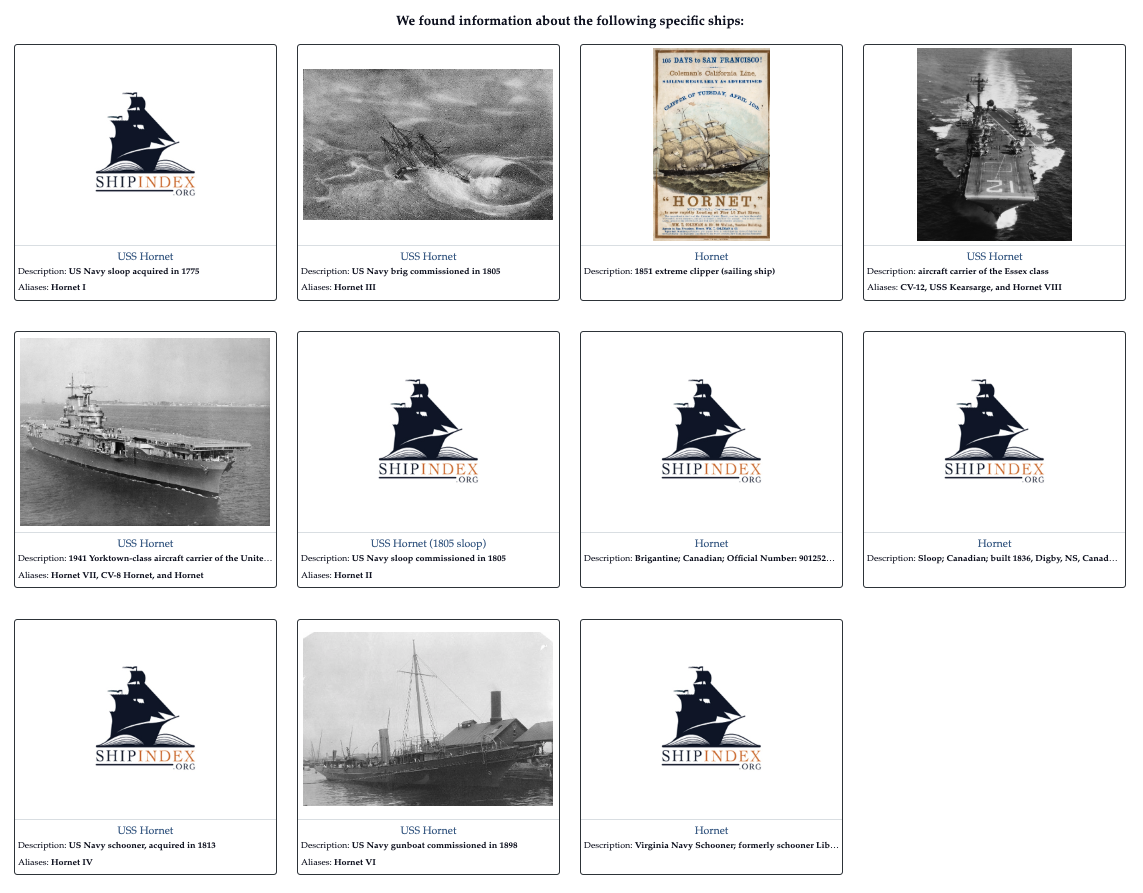

Anyway, when you go to the entry for Hornet in ShipIndex.org now, you’ll see multiple ‘cards’ at the top of the page – each one represents a different vessel, or hull. We pull publicly available data from Wikidata into the cards we create, and we’ll be able to do more there over time. Right now, the images come from Wikidata; when we don’t have one, we have to put in a placeholder. (Imagine a place where you could post your own information, be it pictures, remembrances, links to vessel-specific sites, etc., about a specific vessel. Interested? Let me know.) We organize citations that are specifically about a particular vessel under the appropriate card.

Of course, not every ship in ShipIndex.org has a Wikidata identifier. Right now, we’re using local identifiers when a Wikidata identifier doesn’t exist, or we haven’t found it yet. Since anyone can create a new entry in Wikidata, we can also create identifiers there, and share our knowledge with the rest of the world.

We’ll never get all, or most, or even many, citations associated with cards. “Hornet” has 820 citations from 221 resources. We have 11 cards, for specific vessels, and each card has between 2 and 66 citations associated with it. So, just 235 of 820 citations are associated with cards. But many entries have basically no descriptive information about the ship at all, and one would need to look at each resource to figure out if the Hornet in question is one of the ones for which we have a card. Even when there is information, it’s often not enough – there are nine citations with “aircraft carrier” in the description, but without looking at each resource, I don’t know if they’re referring to USS Hornet (CV-8) or USS Hornet (CV-12).

But for the time being, it’s very much a start toward doing better research in maritime history. Look at the two Hornet links above, for instance. The URL for Hornet CV-8 is https://www.shipindex.org/vessels/Q838125, and the URL for Hornet CV-12 is https://www.shipindex.org/vessels/Q1141355. There’s that Q-identifier again, right in our URL, so it’s easy to find, easy to use, and easy to link to. This is the basis of Linked Data, and of making online research easier to do, and easier to manage.

As of this writing, we have 1446 citations associated with 70 vessels. That’s 0.000409% of all the citations in the database. Admittedly, we have a long way to go! But it is a start, and getting the underlying work done to make this happen was a big chunk of 2019 – it took a lot of time and work and money.

My next goals, beyond expanding the number of citations associated with vessels, is to make a way that users can help grow this resource. Perhaps you have been researching Hornet, and you know that Albion’s Five Centuries of Famous Ships refers to CV-12, rather than CV-8. If you could share that information, to expand the database a bit, that would be huge.

Then, as mentioned above, maybe you have images, or remembrances, about CV-12 specifically, or you want to link to resources about it online (remember, after the current Coronavirus pandemic passes, you can actually visit USS Hornet in Alameda, California; until then, you can visit https://www.uss-hornet.org/) – what if ShipIndex provided a place where you could post those and share them with others interested in researching a specific vessel? That’d be pretty cool, I think.

I’d love to hear what you think about this enhancement. For me, it’s been a long time coming. Of course, there’s much more to do, but I’m very excited about this significant change.