[This entry was written long ago, but not posted, because I was having problems with uploading images. As you’ll see, images are a critical part of this post! Now that I’ve gotten that problem resolved, I will add a few more posts soon. PMc]

Last May, I finally completed one very large file for import. This file was incredibly tough to process, but I learned a lot about how one can use the database, and I thought I’d share that information here.

The database is Mariners and Ships in Australian Waters, and it is a collection of transcribed passenger lists for thousands of voyages to Australia, primarily in the 2nd half of the 19th century. Because most records were handwritten, and then transcribed by volunteers, many, many errors crept into the database.

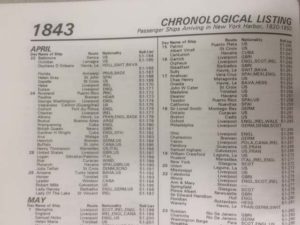

The database has 58,311 records in it. (I believe more are always being added to the website itself, as transcribers complete their work.) One major difference between this and every other resource is that each voyage has a separate entry. In the Ellis Island Database, a user searches by ship name, then goes in deeper by voyage date. In this case, the collection is organized by arrival year, then arrival month, then ship name – so I had to create a separate entry for each voyage, to be able to link to each transcription.

I quickly realized that there were many, many, many errors in the transcription of vessel names. Just looking over the ship names as they appeared in the spreadsheet, it was easy to spot typos – especially with the additional information I had about masters and tonnage, which helped connect a misspelling to a correct spelling.

After correcting numerous such misspellings, I did a test import of the file and found 1707 new ship names would be added to the database. I started to investigate each of those, and found that many were not actually new ship names – they were simply additional mistranscriptions of the passenger lists. As the ShipIndex.org database grows, it’s important to try and minimize the introduction of incorrect ship names.

For example, I saw this entry, which the transcriber recorded as “Maealsar”. The master’s name had been transcribed as “C M de Boer”, and the vessel size as 305 tons.

I thought it looked a bit like “Macassar”, but there were no other “Macassar”s in that file. I did a search in ShipIndex.org for Macassar (http://www.shipindex.org/ships/macassar), and found an entry from the American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping for the same year, and found a Macassar there, with a captain C. M. De Boor, and tonnage of 306. Obviously, these are the same ship.

I corrected the vessel name, but kept the mis-transcription, too, just in case I was wrong. So the entry now looks like this: “Macassar (corrected; listed as “Maealsar”) (of Amsterdam, C M de Boer, Master, 305 tons, from the port of Balaves to Sydney, New South Wales, 23 Mar 1861)”.

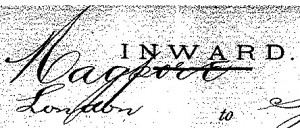

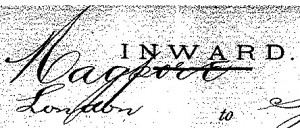

Another example was this name, which had been transcribed as “Magport”:

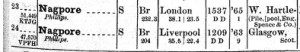

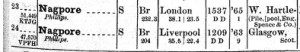

I thought it looked like it started with an “N”, but found no “Nagport” already in the database. However, a search for “nagp*” turned up “Nagpore”, among others, and a link to the entry of Record of American and Foreign Shipping for the same year returned these two ships:

One has the same master and tonnage as the one in the transcription. It then becomes clear that there’s an “e” hiding behind the bar on the page, rather than a “t”.

I felt like it became a combination of genealogy and authority record work. I tried to find sufficient documentation to prove that my analysis was more accurate than the original. And because I had both the entire set of metadata from the source, and the 2.3 million citations already in the ShipIndex.org database, I could more easily determine that various transcriptions were incorrect.

I recognized that ShipIndex.org is beginning to serve as an authority file for vessels. It is certainly my goal to improve the database along those lines, and I will use another blog post to discuss this further.

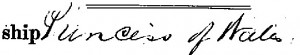

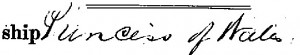

I found many instances of doing this sort of research, and while it took a very long time, it was actually quite fun to nail down a correction. Some were surprising – I guess I can see why one might read this as “Princess of Water”:

But why in the world would you not recognize that “Princess of Wales” makes infinitely more sense for a ship name?

I’ll provide two last examples here. This first one shows how I used the existing metadata for the resource itself to determine the correct ship name.

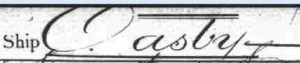

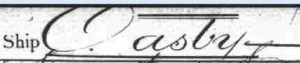

The beautiful handwriting on this one made it easy to read, and it’s not surprising that it was transcribed as “Oasby”. But there was only one entry in the entire file for “Oasby”, and none in the existing ShipIndex.org database, so it made me wonder.

A search through the metadata for the captain’s name, however, found 17 entries with Kennedy as captain (as had been noted in the transcription for this entry), for ship “Easby”, and the full resource has at least 70 other entries for “Easby”. Tonnage data is the same, and after learning of the existence of “Easby”, it’s easy to see that that’s what the ship name was; and the top of the dramatic ‘E’ was lost in the digitizing process.

A search through the metadata for the captain’s name, however, found 17 entries with Kennedy as captain (as had been noted in the transcription for this entry), for ship “Easby”, and the full resource has at least 70 other entries for “Easby”. Tonnage data is the same, and after learning of the existence of “Easby”, it’s easy to see that that’s what the ship name was; and the top of the dramatic ‘E’ was lost in the digitizing process.

This made the next new ship name, “Oaton Hall”, easy to resolve to “Eaton Hall”.

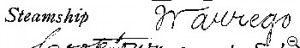

Finally, I dealt with this challenging entry by using the existing ShipIndex.org database:

I tried searching for “waurego”, but that returned no ships. By searching for “*rego”, I found all the citations that had a word in the ship name that ends in “rego”. I could easily locate “Warrego”, and confirm that’s the right ship.

I tried searching for “waurego”, but that returned no ships. By searching for “*rego”, I found all the citations that had a word in the ship name that ends in “rego”. I could easily locate “Warrego”, and confirm that’s the right ship.

There’s other searching that could be done here, too. If I change the search to “*rego$” it returns only the ship names that actually end in “rego”, deleting several, like “Trego Renneger” or “Effrego Ventus”, from the result list.

I’ll put together another post in the next few weeks with more examples of changes and corrections I was able to make, along with a discussion of the importance of authority data for ship names.